The election of Nov. 5 will be marked as the year that Donald Trump regained the presidency, but Saginaw’s local campaign for a quintet of four-year City Council terms was among the closest ever. The five winners all gained between 4,500 and 5,500 votes, and six others came within 800 or less of victory. This would have reaped far more attention if there still were city-only elections in odd-numbered years, like the landmark civil rights ballot of 1983 that is reviewed in the following documentary report. Local voter turnout declined sharply near the millennium’s turn, and a 2013 change was made to the bottom of the ballot for even-numeral bigger federal and state elections, like we had here in fall 2024. Do you like the old city-only elections, or do you prefer the new format?

SAGINAW, MI — Four decades ago, the Saginaw election of November 1983 produced the first African American majorities to serve on the City Council and the Board of Education.

Locally, this occasion was celebrated somewhat like President Obama’s national victory a quarter-century later. A mountain had been climbed.

One individual is absent from official records, even though he had a prime role. Oliver Bruce Moorer was not among the six black candidates who won office as part of this major chapter in Saginaw civil rights history. He had lost his life by then, but his legacy remained alive in every polling place.

To begin the scenario, Moorer was 41 years old when he was slain April 23, 1981, in a torrent of police gunfire during a middle-of-the-night drug raid by an all-white SWAT team with a warrant for marijuana at his residence, 1911 Cherry.

From the first day, an “enough is enough” outcry arose, like Black Lives Matter ahead of its time. The man who died at the hands of city police was well-known and highly-regarded among minority citizens as a 1960s and ’70s activist who had evolved to become the county jail’s first black probation officer.

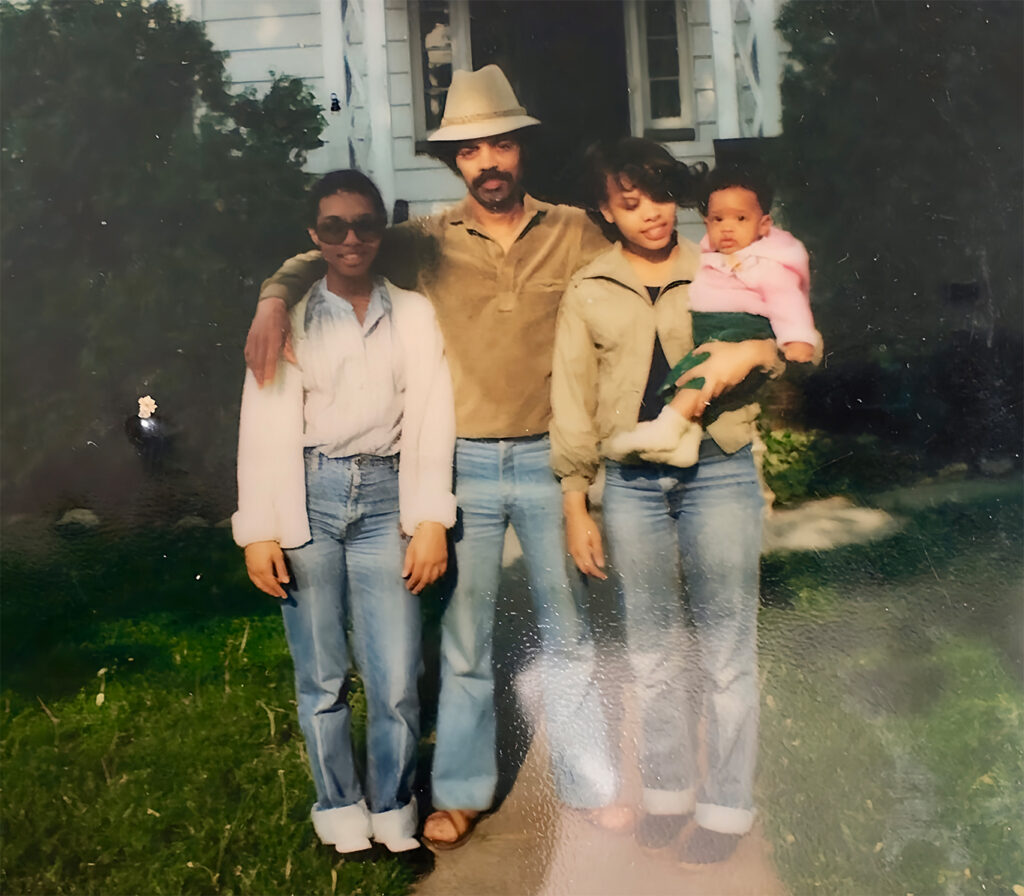

Celestia Moorer-Brown, eldest of his six children, recalls when their father would take them bowling or to summer ballgames, and “everyone would honk their horn at him, and he would honk back, because he knew everybody else.”

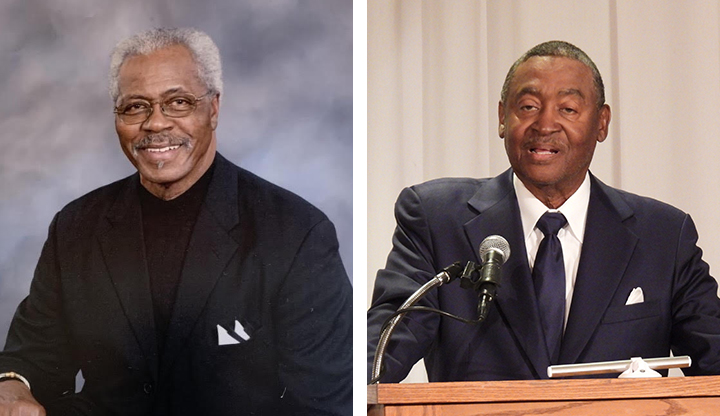

Therefore, “it was the Bruce Moorer election” in 1983, asserts Larry Crawford, condensing the mutual memories of council peers like Carter McWright and later, Gary Loster, who were leaders during the time of turnaround, and who are sharing their thoughts at the anniversary.

In fall 1981 at the polls, the community’s response to the slaying began with re-election of Joe Stephens, along with Crawford, a newcomer who would be followed by the big surge two years later. Stephens had served as the second black mayor, following Henry Marsh’s footsteps. Crawford soon would become third in line.

But the Moorer groundswell didn’t have time to fully develop in time for the ’81 vote, Crawford explains, and momentum grew during 1982 and 1983 as the slaying more and more became Saginaw’s last-straw symbol for years of oppression in the name of law enforcement.

Citizens absorbed the scenario, all too familiar, as officers were exonerated after an inquest, in large part based on their assertions that Moorer had fired first through closed front doors, forcing their onrush and repeated rounds of fire. His supporters responded that even if true, most people would react the same, figuring these were robbers, not cops.

With two more Moorer years for the reality and facts to sink in, these were the November ’83 election results:

- On the City Council, mid-term incumbents Stephens and Crawford were joined by Mildred Mason, Lou Oates, Joy Hargrove and Carter McWright to hold six of the nine seats, only 22 years after there had been zero minorities.

- On the Board of Ed, pioneers Ruben Daniels and Willie Thompson welcomed Hazel Wilson and James W. Woolfolk Jr. to the table. A short 15 years earlier the seven trustees all had been white, and now four faces of color suddenly made up the majority. Mason, an educator and businesswoman, and Wilson, a social worker both professional and volunteer, were the top vote-getters as women began to emerge.

Voting matters

By no coincidence, this was the first time East Side blacks ever had outvoted the West Side, which in 1983 remained more than 90 percent white during the first stages of cross-river neighborhood integration. The inspiration for this new voting outbreak, surviving participants agree, was the furor over the Bruce Moorer case, with spinoff from the council election affecting the school board.

At City Hall on election night, results gradually were posted on a raised TV in council chambers. Totals grew precinct by precinct. Black activists gathered mainly in one corner and began to celebrate the victorious breaking news. Whites, huddled across the room, still carried hope that at least twice-appointed Del Schrems would keep his place for the final elected spot.

But then Arthur Eddy was slow to arrive because of record heavy turnout, and when the screen showed McWright rallying from behind to capture that last seat from Schrems, the scene mixed one group’s arms-raised joy with the other section’s astonished silence.

(Historians note that back in 1955, the early numbers indicated Harry Browne was going to win, becoming the pioneer, until a big load of late votes came in from another Arthur, in this case Arthur Hill, with backing from the white-collar “Committee of 50,” later United Saginaw Citizens. And so 28 years later, in 1983, the same fate happened to Schrems in reverse as had been for Browne, reflecting the tide of change.)

But there’s a downside. The 1983 East Side voter turnout turned out to be a one-time thing, burning out before the decade ended, declining even more sharply here on the 21st century side of history.

By 1985 Schrems was running again, with yard signs that showed not only his name, but a slogan: “Balance the Power.” This, he explained, was “the same as what black people have been saying all these years when they were on the short end.”

That November, Schrems was the West Side’s leader in the totals, but the power was not immediately balanced. Other winners were Crawford, Roosevelt Ruffin, and Randy Jurrens, keeping the 6-3 ratio.

But the white backlash and black apathy reached full fruition in 1987, with East Side turnout further falling to barely half the ’83 headcount, Oates and Mason were voted out of office, and McWright didn’t run again, already frustrated and soon to move with his Music Planet store to Flint. Schrems subsequently was appointed mayor by the restored white majority.

On the ballot’s other portion, Thompson in ’87 was voted off the school board. His demise was not from opposing votes, but from a lack of supporters at the polls.

A single-issue election

No Saginaw election, before or after, has come down to one “big thing” that dominates public response in any similar way to the Moorer slaying, not even after city police in 2012 gunned down Milton Hall in the Riverview Plaza parking lot.

Even future voters were affected by Moorer’s death in 1981. Elbony Washington, an 11-year-old neighbor at the time, recalls the drug raid as an “ambush.” From her home in Seattle, she said recently, “As a child, it had me devastated. I can remember clearly entering the house where he was killed shortly after the investigators had cleared out. I can see the red blood on the pool table (where he died) as if this had happened yesterday. Mr. Moorer is a hero in my eyes and in his honor I’ve made a choice to stand and speak up against injustice.”

The East Side’s strong showings at the polls after 1983 were not local, but national. Rev. Jesse Jackson visited during his groundbreaking bids for the presidency in the 1984 Democratic primary and then again in ’88, when he won a stunning Michigan victory with overwhelming Saginaw support, only months after the Mason/Oates/Thompson defeats.

Although Loster didn’t fully emerge in city politics until the 1990s, he observed the 1980s as a Vietnam vet who had served a stint as Buena Vista’s police chief before he enlisted with General Motors security. The level of local interest “has never been the same since the Bruce Moorer case, and then for Jesse Jackson, for whatever reason,” he says.

A contrasting scenario

Compared to the tragic fate that befell Milton Hall, there were (and are) no videos of what happened to Bruce Moorer that spring evening on Cherry near South 13th. Even so, the outlook among most black citizens was, he was interrupted from sleep and, if he fired, he fired as a natural reaction, especially given his line of work.

Did four cops really need to barge in and fire more than 30 rounds in return? Besides, a neighbor testified that after the first shots, she heard Moorer plead for mercy with shouts that he had not realized they were vice officers, and he had attempted to surrender during the start of the return spree of bullets, to no avail.

In most residents’ eyes, there may as well have been a tape.

Celestia Moorer still was a teen at the time, but as the case and the commentary evolved, she immediately started filling scrapbooks with clippings from both The Saginaw News and The Detroit Free Press, which had picked up on the story. She recalls, in retrospect, that her father had become quiet and distant during the final weeks, as though he foreshadowed the tragedy that was ahead.

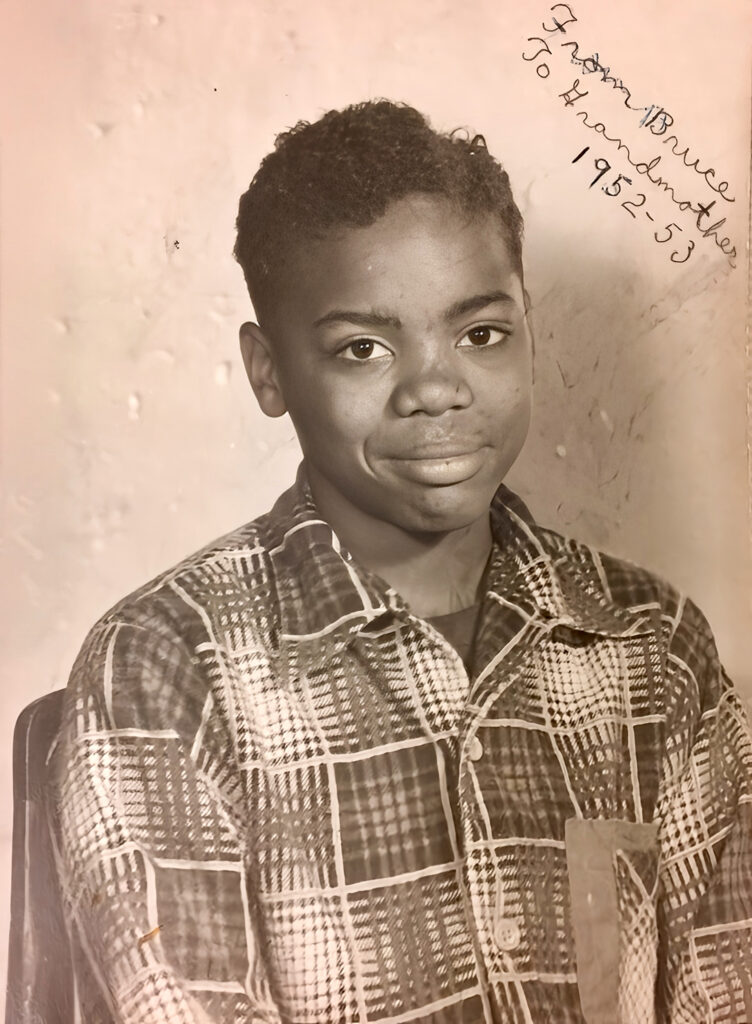

Milton Hall was a helpless homeless man. Not Bruce Moorer, among the first mid-1950s students at then-new Saginaw High School. He enlisted in the Army and returned for work at the Chevy Parts Plant on East Genesee during the 1960s, and started his family of six children.

Still, he found time for studies at what then was Saginaw Valley College, SVC, with degrees in sociology and psychology that freed him from the auto-plant grind and led to his second career as a parole officer.

Moorer was involved in Model Cities discussions, similar to today’s ARPA, for the federal War on Poverty, mostly through the newly established Saginaw County CAC. He formed a group called “Why Can’t We Live Together?” and taught a class in community organizing at the Delta College St. Joe’s Center.

He declared in a Saginaw News report on April 22, 1973, “If City Hall won’t come to northeast Saginaw, then northeast Saginaw will come to City Hall.” This was eight years and one day before he was slain.

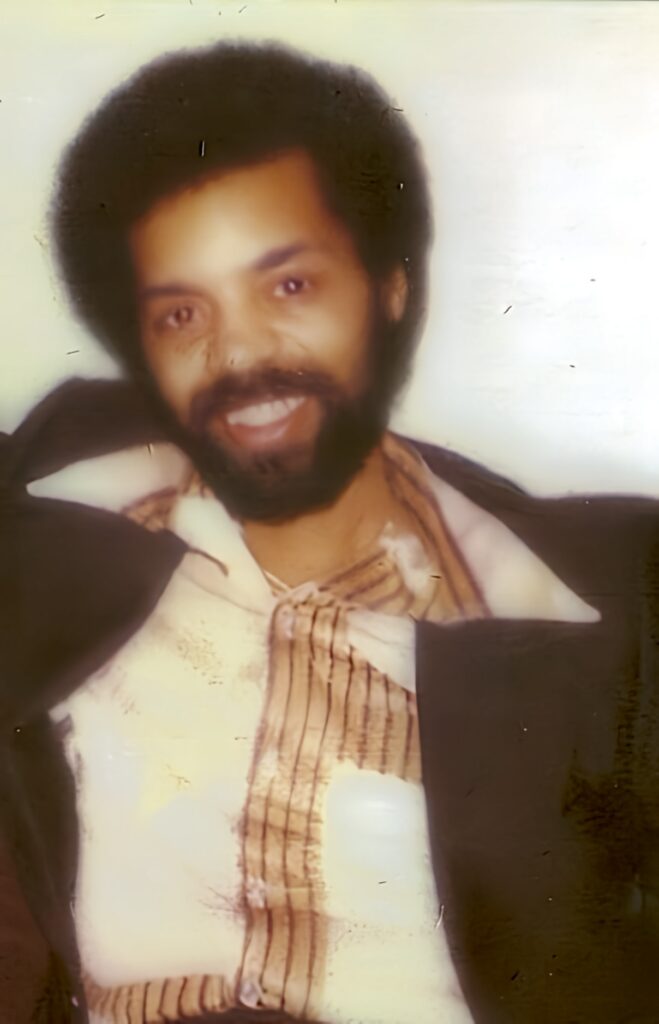

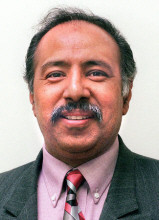

Moorer again was featured in a Nov. 14, 1976, newspaper profile, this time at his courthouse desk, adjacent to the jail. A photo showed him in disco-era polyester attire, and correspondent Venice Holmes wrote about how Moorer could relate to the clientele, having himself been busted during prior times, socializing at after-hours establishments along Potter Street or in the neighborhoods.

The section-page profile, more deeply, demonstrated that the hip new probation officer wasn’t only teaching community action, he was engaged in it himself. A main opinion he expressed, more than once, was that City Hall was far too slow in recruiting more minority police officers.

Days after Moorer was killed, five members of the Black Police Officers Association helped carry the casket during a memorial service that overflowed Bethel AME Church. They were Ernie Bradley, Henry Hopson, Bill Washington, Al Jamison, and John McAfee.

Each in the quintet refused remarks for media members who asked why they were paying tribute to someone who allegedly had fired shots at brethren officers. The five had spoken with their actions. Meanwhile, the Black Business Association raised funds for legal proceedings.

Lee Elsenia Porterfield, a South Sider who took her ever-present foster children and her knitting to the Human Relations Commission meetings, was among letter-to-the-editor authors. She wrote that Moorer “went to the same church as I do, and he took his children. He spoke to the congregation about his love for his mother, for his family, and for the people of Saginaw who needed a helping hand.”

Patricia Mosley wrote, “Mr. Moorer’s death has only served to reawaken the East Side citizens, and these emotions will not blow over, and our voices will not be quieted until justice is done.”

White letter-writers responded that race-based sentiment against white police was unfounded, and that lawbreakers always have only themselves to blame.

Latinos as third parties

No Latino candidate emerged in 1983. A blowup had taken place a few years earlier on the school board side, when trustees appointed Gilberto Guevara to fill a vacant seat, only to have the interim city manager, Bob Dust, issue a debatable declaration that the City Charter prohibited municipal employees from holding any sort of public office.

In January 1985, when constant nemesis Walt Averill III resigned, the new council took a new step toward three-way ethnic makeup with the appointment of attorney J. David Perez, 26, fresh out of law school and even younger than Crawford, Mason, Oates and McWright.

Perez had only 10 months to make a name for himself and fell short, middle of the pack, in the November 1985 election. He never re-joined local politics or community affairs, saying at the time he felt “like a ping-pong ball” being knocked back and forth by local special interests, both black and white.

(Vernon Stoner, named first African American city manager in 1987, upon departing four years later remarked, “For many people, I was too black for the whites, and not black enough for the blacks.”)

For the 1993 elections, Guevara reappeared as leader of “Hispanics for Better Government,” resulting in the first two Latinos elected to local office.

Popular volunteer Minerva “Minnie” Rosales invested six frustrating years on the school board, home to no other Latino trustees before or since. Superintendent Foster Gibbs and other board members would ask for specific proposals geared to Latinos, and she would respond that she could offer advice with her advocacy, but that she was not a professional educator and that the task ultimately was up to Gibbs and his team. The lowest moment was when she protested with a spontaneous walkout during an all-day planning session.

Dan Soza Jr. attained a council seat in tandem with Rosales. He was a more traditional liberal and managed smooth relations with most of his City Hall peers, even commuting with Joyce Seals to work at MSU in East Lansing. He closed his 12-year tenure by rounding up support from Council members two decades ago, both black and white, to transfer ownership of an historic city-owned home across from Hoyt Park as a community center for the newly-formed Mexican American Council.

Was there justice?

With Moorer, as with Milton Hall three decades later, there were no criminal prosecutions. Families received civil settlements — $350,000 for the Moorers, and $725,000 for Hall’s mother, Jewel. They had sued for more than $20 million in each case.

City Councilman Walt Averill and other conservatives who had pushed the 1979 frozen property tax caps, which still are in place, protested the money for the Moorers. Jerome McKenzie of Saginaw United Taxpayers said it was the police who should be reaping the cash settlements instead, suggesting something in the range of $100 million, a statement that was part of the racial split at the time.

To face up to the protests, then-City Manager Tom Dalton within 24 hours announced an independent probe. He also halted such aggressive drug enforcement tactics as moonlight raids and undeclared door knocks. This was similar to the Louisville 2020 follow-up to Breonna Taylor’s death.

Under the black majority from the ’83 election, Dalton assigned Labor Relations Specialist Ralph Carter to develop recruiting and training policies with specific numerical targets for race and gender integration in both police and in fire, resisting (and sometimes settling) reverse discrimination lawsuits from whites who didn’t receive promotions.

This didn’t mean there would be smooth sailing. During the years between the Moorer and Hall slayings, a major incident involved two white off-duty officers who kidnapped a teen who they claimed spoke something sexual to one of their wives from a neighborhood sidewalk near Arthur Hill High School, where many police resided, still bound at the time by a residency requirement. The young man testified that the officers forced him into their trunk and dumped him on the other side of the river. Outrage occurred, along with a mix of silent thanks that an Emmett Till-type tragedy was not carried out.

City Manager Tim Morales and Police Chief Bob Ruth both took office in the aftermath of the Milton Hall tragedy and have aimed for reforms. City police ranks now are one-third minority and/or female, although the impact is lessened by the higher reliance on less-integrated state police. During a public forum last spring, complaints focused on MSP traffic stops even beyond the publicized incidents on Annesley and then Webber streets.

Also, Saginaw’s part in the nationwide protests that followed the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd led the prior City Council in 2020 to establish by ordinance the Citizens Police Advisory Commission, CPAC, which has met bimonthly for three years but has not staked out any policy or reform positions in a similar manner to the old Henry Marsh-inspired Human Relations Commission, which was active in the Moorer case along with day-to-day grievances based on race.

(Three years before his election to City Council broke the color barrier, Marsh in 1958 had ruefully nicknamed HRC as the “Bar Commission” while he served as founding chairman, because so many complaints regarded refusals of service in taverns and nightclubs. In one case, a recalcitrant bar tender/owner “complied” by indeed serving a customer of color, but then shattering the emptied glass against a wall so that no white patron’s lips ever would be “soiled.” The Elks Club, formerly across from the Potter Street Station, now is located in the former Plant 8 Lounge.)

Joe Stephens speaks out

African-American council members who took the 1983 post-election lead for public safety integration — Crawford, Mason, Oates and McWright — were from Bruce Moorer’s generation or younger. Their mentors and elders included Stephens and Marsh, who encouraged a lower-key approach to pursuing change, rather than weekly council-table orations on the need to reform the cops.

But it was Stephens, generally conservative with original Committee of 50 backing, who ended up taking the most strident public stand. A former police officer among the first to integrate the force, he was not popular with some of his white peers downtown to the point where as mayor (1977-79) they posted a traffic ticket on his windshield when he parked behind the Civic Center for a quick ceremonial entry-and-exit to a Wendler Arena event.

He thus believed police leaked a 1984 report to news media that he owned a private operation, Gibraltar Services, that provided security at an after-hours club on East Road named “Do Drop In.” This was learned from a vice raid.

Angered, Stephens countered months later with a public allegation that several unnamed Saginaw police officers were engaged in sex crimes, theft of evidence, false reports and use/sale of illegal drugs seized from citizens.

An appointed three-member panel for a closed-door probe included two out-of-towners and Saginaw attorney M.T. Thompson Jr., future county judge. The investigators found evidence to support some of Stephens’ claims, but no criminal charges were filed or grand jury formed, similar to the previous Bruce Moorer case and then Milton Hall in the future.

Findings were kept private by court mandate, and neither Thompson nor any of the six black council members would agree to “leak” any details to news media, not even anonymously. This was done instead by a white councilman who perceived that the report summary, overall, would build public confidence, among all ethnic groups, in city police and their conduct.

Aiming to compromise

Police reform may have been the driving force behind the unprecedented African American voter turnout in 1983, but of course this was not alone on the agenda. While the newly empowered black leaders stood strong on integrating the law enforcement ranks, their strategy otherwise was to demonstrate that the remaining white city dwellers need not feel excluded by the new experience of others holding the helm.

In effect, the new council reached out to whites far more in full than whites had reached out to them through the years:

- One olive branch was to expand federal block grant target zones for the first time into lower-income neighborhoods on the near West Side, so that someone on Harrison Street could qualify for a home-repair grant, for example, the same as a resident in need near Sheridan Avenue.

- Another plan was to devote 1 percent of the general fund budget to arts organizations, with full inclusion of traditional white-oriented groups like the symphony and the choral society. Budget shortfalls soon stopped the full amount, $250,000 at the time, but the old Andersen Pool shower space was converted to today’s showcase Enrichment Center, and the Arts Commission was formed.

- The moniker “Celebration Square” was created so that the central parks would not be thought of so much as East Side, and the script “Saginaw” lapel pins first became trendy, a small first step toward creation of the Saginaw Future agency for economic development.

- For the ever-present 1980s question of tax breaks to help save General Motors, the black members generally stood with the Chamber of Commerce in favor. Only Oates joined Sister Ardeth in left-wing opposition, bringing Ralph Nader’s watchdogs to town to help advocate against abatements. Crawford summed up reasons to stick with the establishment when he noted that without the tax breaks, GM full well might move Saginaw operations to Ohio or Indiana or Mexico. This happened anyhow, but the question seemed still up in the air in 1983.

Double standards

The wave pool later in the decade was a fast failure, with the black council members blamed and ridiculed, but this idea was not from them, but from Frank Andersen himself, with former Mayor Paul Wendler at his side. How were they supposed to say no to a generous civic giant who donated the first $1 million for his final wish after his 100th birthday, which was to replace the worn out municipal swimming pool in his name with something more modern to promote “urban tourism?”

This didn’t seem so far-fetched back then. Saginaw even seemed ahead of Frankenmuth. By the time the water park opened in 1988, Crawford had resigned as mayor to pursue his business interests, and it was Schrems who took the inaugural ride down the slide.

The $3 million grant- and gift-funded construction was not questioned; instead, it was the annual operating cost from the general fund. This was seen as a double standard among black leadership, because nobody ever questioned the annual tax subsidy for the old Andersen Pool with its 10-cent admission.

Other examples:

- When members, especially Oates with Sister Ardeth, followed larger cities in adopting a local divestment ordinance in protest of South African apartheid, they were accused of going beyond their assigned local duties. However, when Carol Cottrell as mayor won support years later for a resolution against the Iraq War, no similar level of disapproval came forth, displaying another double standard.

- In the same vein, the new council was downgraded for occasions of public discord. It turned out that black politicians not only didn’t always agree with one another, they also ironed out things openly, not secretly at the Saginaw Club, as had been white professional precedent.

There was not the same sort of criticism only a few years earlier, the first and final white public battle among United Saginaw Citizens, with Paul Prudhomme and Ron Bushey in 1979 haggling for four weeks over the mayorship. The final ’79 compromise was for Prudhomme to take the immediate two years as mayor, followed by Bushey for the next pair.

There also were inner conflicts. Hargrove was a Republican who drew self-attention by aiming to simultaneously serve on the County Board. Stephens, with a home on the Ren View subdivision’s new Martin Luther King Drive, blocked a McWright effort to follow national trends and rename Genesee Avenue, both east and west, in a larger tribute, dubbing him “Carter McWrong.”

Crawford started the trend for multi-term mayors when he changed his mind in 1985 at the last minute on giving Mason a chance to become the first woman, later achieved by Wilmer Jones Ham. Gary Loster ultimately attained four two-year mayor terms in a row.

On the school side, one foretelling event was the vote to close Potter Elementary, especially emotional for alumni Daniels and Thompson, who insisted on doing the deed not in the downtown board room, but in the gym at 10th and Farwell, out of respect for the remaining residents who attended. There were explanations that Potter’s loss would not be alone because population trends showed more mothballs to come, but the sweeping decline that followed (closing Edith Baillie, Longstreet, Houghton, Morley, Heavenrich, Emerson, Jones, Longfellow, Webber, Salina, Coulter) was fathomed by few in advance.

(The late 1980s seemed for a moment like the 1960s when the empty Potter structure was scheduled for the wrecking ball, and activist Bobby Stitt chained himself to the entrance in a protest that endured for several days.)

What caused voting drop off?

After her 1987 backlash ouster from the council, Mason spoke in “us and them” terms regarding blacks and whites in leadership. “We tried to work with them,” she said, “but despite our outreach, they turned us away.”

Crawford at the time theorized that some black people became disenchanted because they expected mass employment to result from the 1983 election’s local power flip, but this was at the same time that Reagan Republicans were chopping federal revenue sharing grants to cities that had paid for some of those jobs, and so he felt the ’83 council was blamed for actions the national GOP took during their years in the majority.

Henry Nickleberry, who would become the fourth black mayor in 1989, said a ward system was an answer to address the apathy, an idea that still is floated from time to time, along with an elected mayor.

As then-Saginaw NAACP President Bernice Barlow lamented, “By the time white people fled and allowed us to share power, the cities already were becoming decimated, so thanks a lot.”

Henry Marsh pointed to the theme of blacks needing to be “twice as good” to overcome obstacles to equality, in the perceptions of ethnic peers as well as the eyes of whites, asserting, “We are harder on ourselves.”

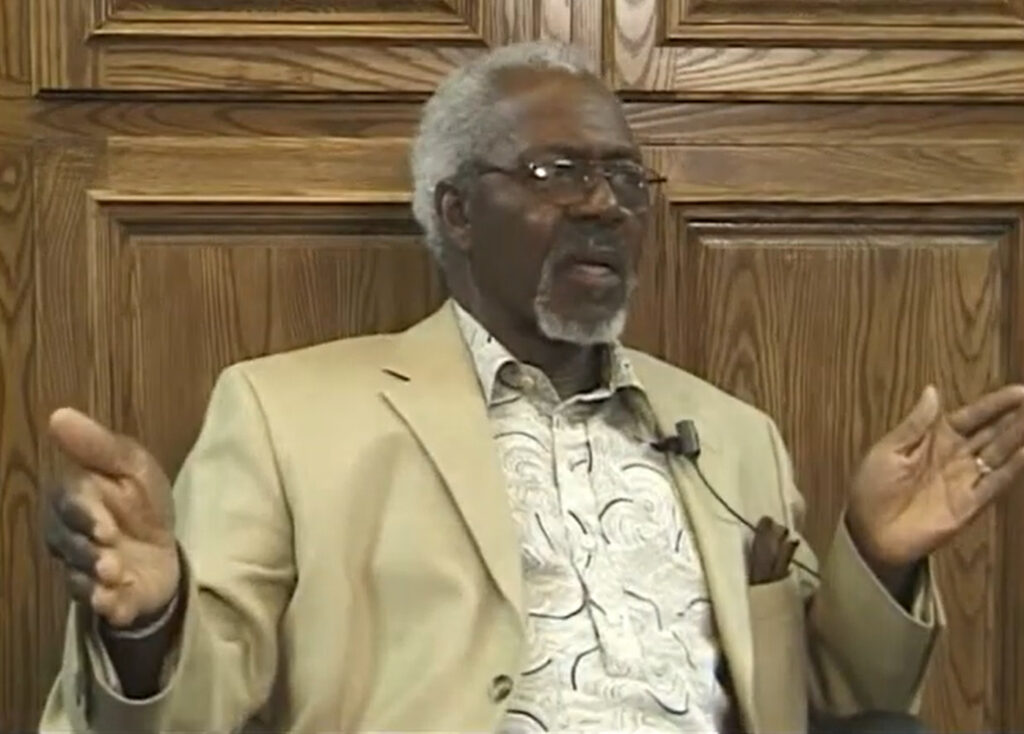

Willie Thompson, the only 1987 defeated candidate to stick with it, returned for a 1989 bid, campaigning as though he was a newcomer rather than a respected elder to win back his seat, serving until his death in 2005. Wife Mattie and son Jason followed his footsteps. Part of his analysis at the time was that many everyday citizens had switched to audiocassette tapes and no longer tuned to WWWS-FM, now KISS 107, for election day get-out-the-vote radiothons, with the Rev. Roosevelt Austin hosting from the Zion Baptist gymnasium and joining activists like Al Loveless, John Pugh and Rosa Holliday over the airwaves during the 13 hours of polling. As a Delta College professor of sociology, Thompson’s overall analysis was far more in-depth, but this was an example of the dilemma.

(In one of the few community-driven actions of recent years, Holliday organized petitions to rename Second Street as Roosevelt Austin Avenue.)

Back to basics

Pastor Austin, who joined Marsh and legal partner Carl Poston on the City Council during the later 1960s, advocated for black voter registration in his Louisiana hometown of Opelousas during the early 1950s, even prior to the Montgomery bus boycott. One of his four cohorts was killed by the Ku Klux Klan, and he realized that he just as well could have been the victim.

When he moved to Saginaw with Nurame, his wife, he vowed never to miss an election, be it a big presidential ballot or a mere local vote.

“I was fighting for my rights,” he noted in a final interview, “even if I had to risk dying in trying.”

In signs that decline has extended into the 21st century:

- Carl Williams barely missed out on becoming Saginaw’s first black state senator in 2006, after breaking the state rep barrier six years earlier, losing narrowly to Roger Kahn because East Side turnout was a scant 15 percent, compared to 33 percent west of the river.

- Even when Barack Obama achieved his historic triumph for president in 2008, and repeated in 2012, East Side turnout was less than 50 percent.

- More recently, for the school millage approval in 2020, mostly for Saginaw United High, the wide margin was attained on the West Side, with the East Side nearly deadlocked in comparison.

Today’s lack of participation has become so dire among all ethnic groups, especially Blacks, that separate city elections in odd-numeral years like 2023 have been merged into even-numeral years (2024 for president, ’26 for governor, etc.) so that more people will show up beyond 15 percent.

That’s why there was not a city-only election last fall. In effect, the same ballot that would have been alone last fall was on the back of the sheet, behind Harris and Trump, behind campaigns for Deb Stabenow’s and Dan Kildee’s successors.

Covid is not to blame because the shorter election lines had taken root long prior. And it’s not like people don’t want to get involved, because summer events like the African Cultural Festival and the Gospel Fest, even the third annual Unity in the Community Kickball at Hoyt Park, drew large post-pandemic audiences this summer.

There’s simply something more challenging about persuading people to participate in voting and political action. City, school and county “liaison” members have adopted voter registration as a top item for future joint efforts and outreach, but they have not contemplated any sort of return to city-only elections, like the landmark in 1983.

What would the elected “Class of ’83,” along with community organizer Bruce Moorer, have to say 40 years later, in regard to the sagging voter outlook that has taken place since their time?

For reader responses, please email mwtsaginaw@yahoo.com.

For a documentary view of another local benchmark, the summer of 1967, by Isis Simpson-Mersha (not responsible for putting ‘riots’ in the editor’s headline), click here.

Comprehensive black histories are available at Hoyt Library for 1855 to 1900 (Dr. Roosevelt Ruffin), and 1900 to 1960 (Dr. Willie McKether). This special report from Saginaw Daily is a contribution, along with Isis Simpson’s writeup, to compile post-1950s archives.